The Consecration of the Goat Mask (Li Sacre du Maske-Chievre)

In Gallia, when the longest night settles over the forests and the breath of winter stills even the streams, the people gather for the Rite of the Goat Mask. This custom is not a somber ritual, nor a celebration. It is something in between, a dance of memory, as old as the first paths Meirothea opened through the dark.

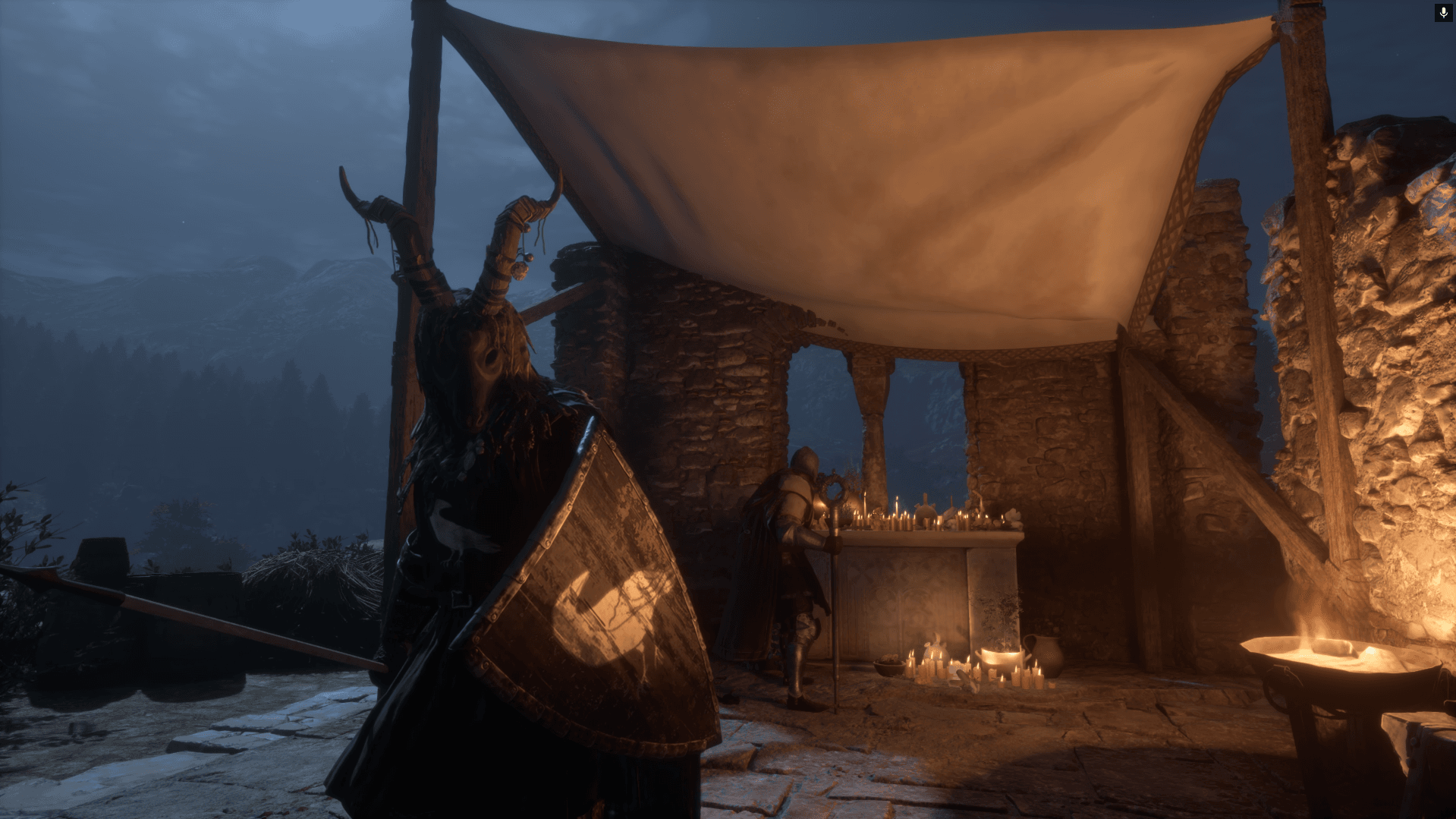

At the height of the Yule feast, the fire is quieted and all lights but one are dimmed. From a wooden chest, worn smooth by generations, the Goat Mask is lifted. Carved in the likeness of Meirothea’s guide, bearing her symbols, it is passed into the hands of the first performer.

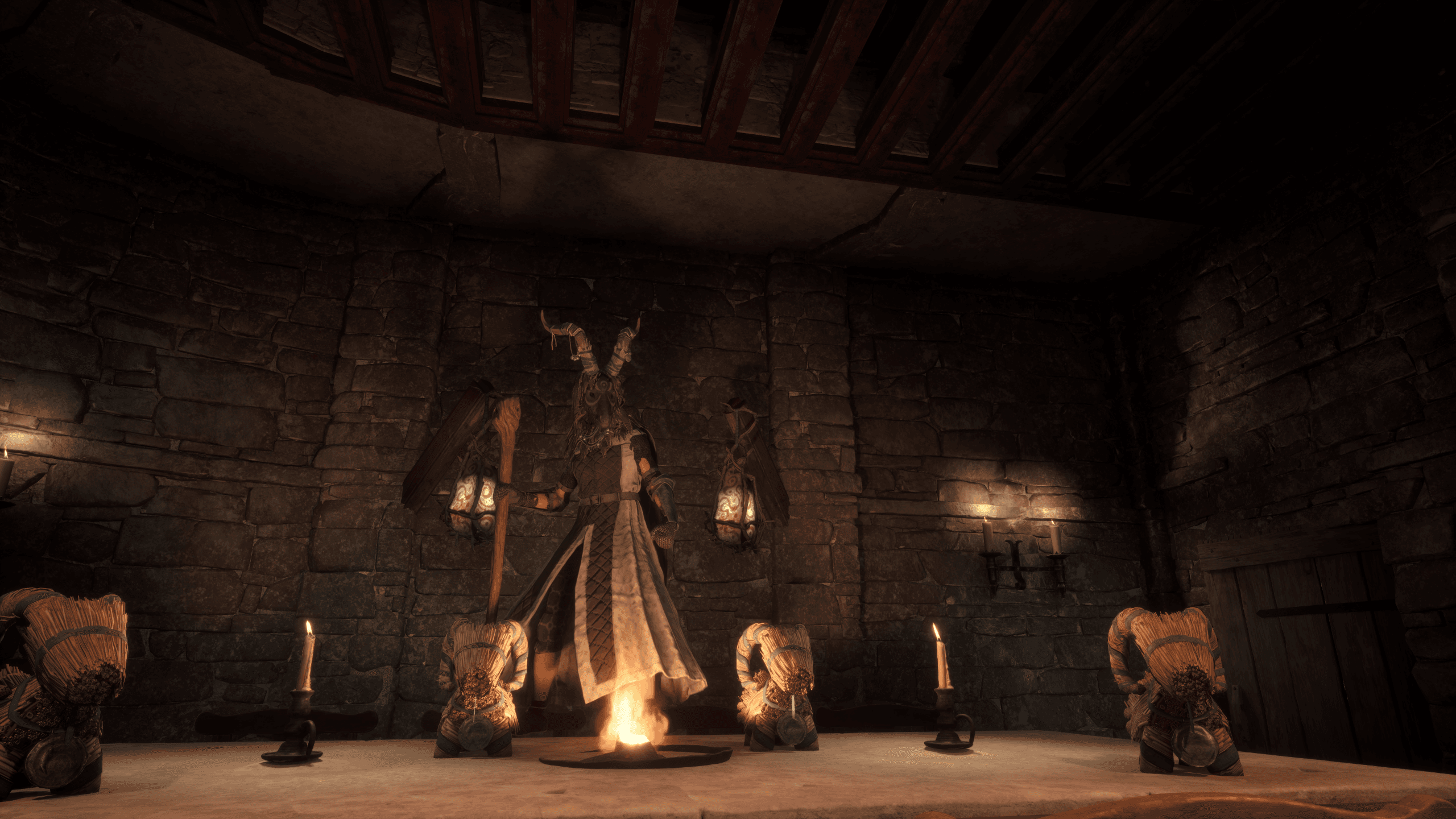

When the mask is worn, the wearer becomes “the Goat.”

Not a person, not a villager, not someone bound by debts or quarrels or pride.

The Goat is a voice for the dead, free of judgment, free of shame, free to speak truths that living tongues often swallow.

One by one, those who take the mask must offer something to the night: a tale of someone who passed beyond the Veil this year, a song they once loved, a dance that echoes a shared moment, a poem that frees a buried grief, or simply a memory too heavy to carry alone.

Laughter is welcome. Tears are welcome. Silence, too, is welcome. For behind the mask, no one knows who speaks, and none may hold a grudge: Gallians say, “Chievre qui parole. Nuit qui prent.” What the Goat says belongs to the Night.

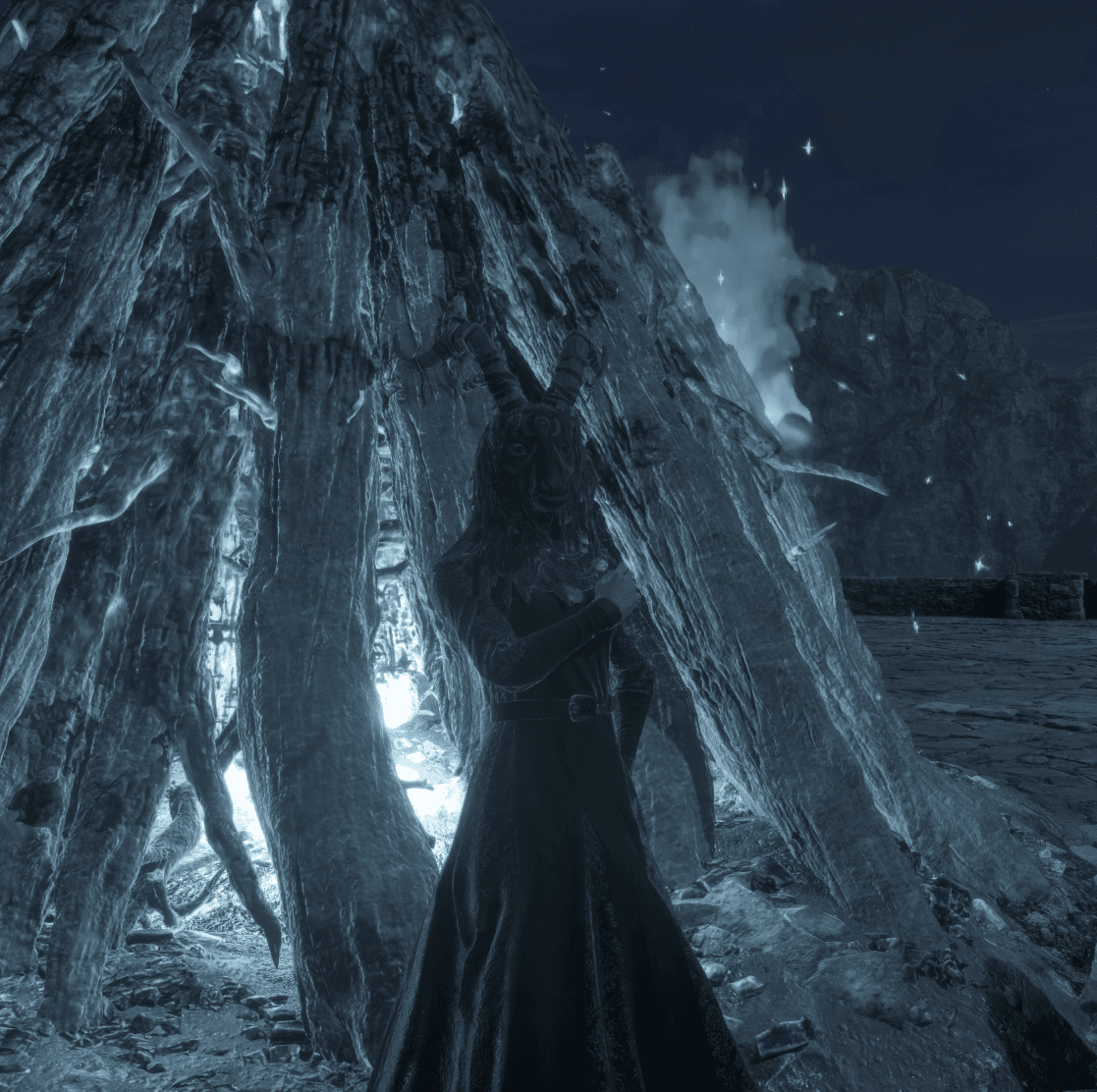

When all have spoken, danced, sung, or simply breathed out their sorrow, the final bearer of the mask steps outside into the cold.

There, they raise the mask toward the sky and trace a slow circle with it. It is the circle of the goat’s ancient path, the one believed to lead spirits from the world of frost to the moonlit road beyond the Veil.

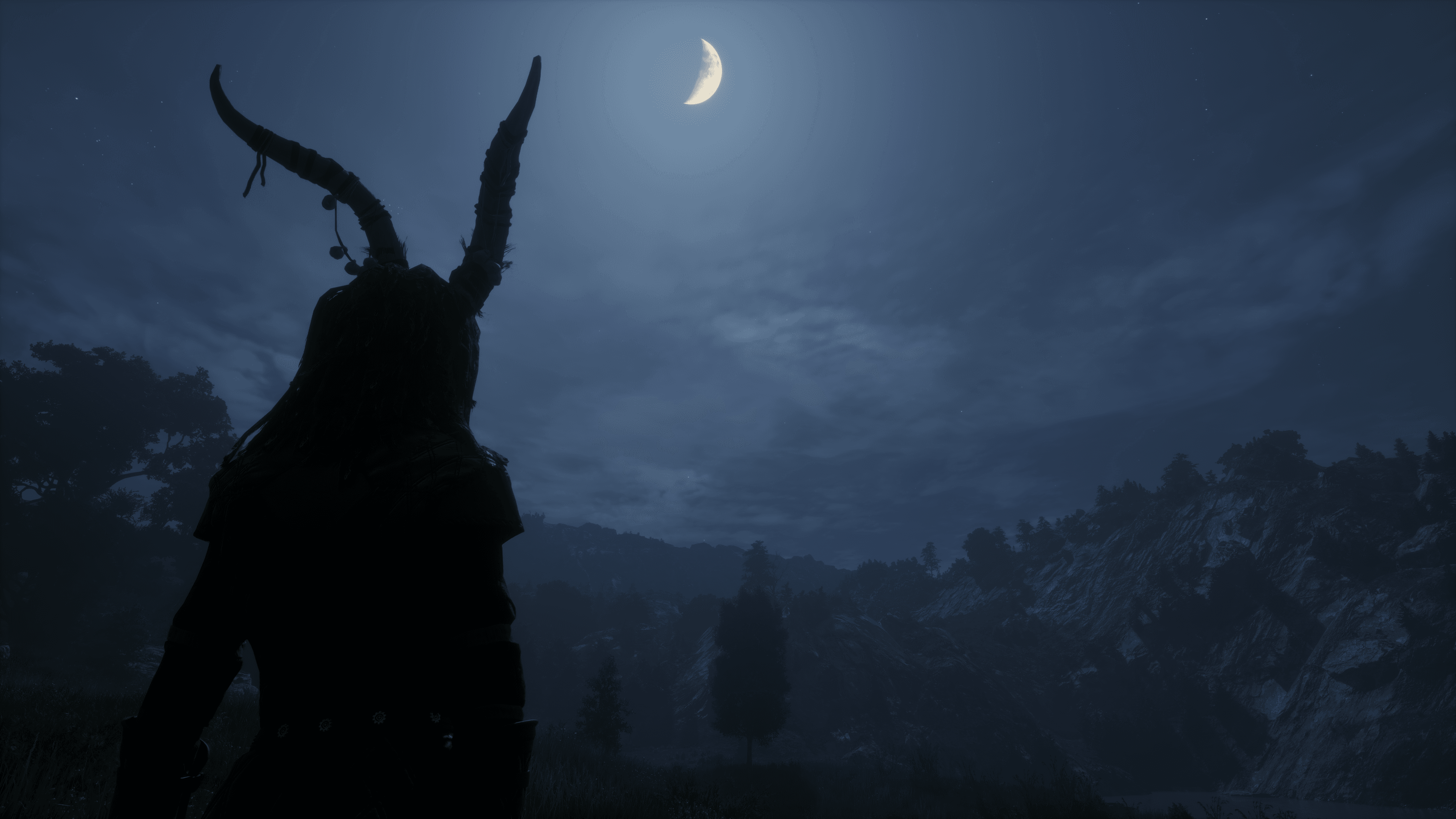

Then the mask is lowered.

The lantern is brightened.

The fire roars again.

And the Goat’s work is done for another year.

Gallians say that on this night, the spirits walk lighter, and the living do too.